President Yoweri Kaguta Museveni has called for a shift from historical claims toward a more inclusive and development-oriented approach in managing the Nile River, urging cooperation among all Nile Basin countries to ensure shared prosperity.

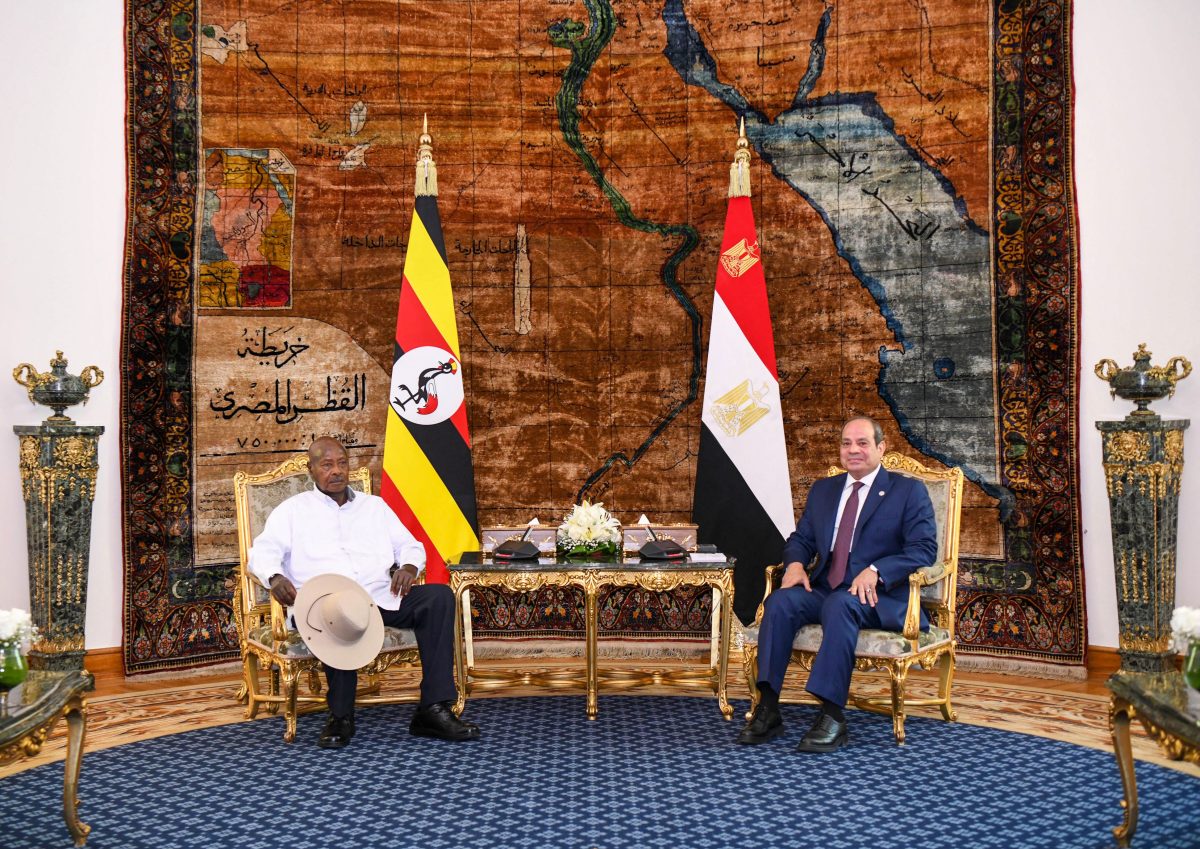

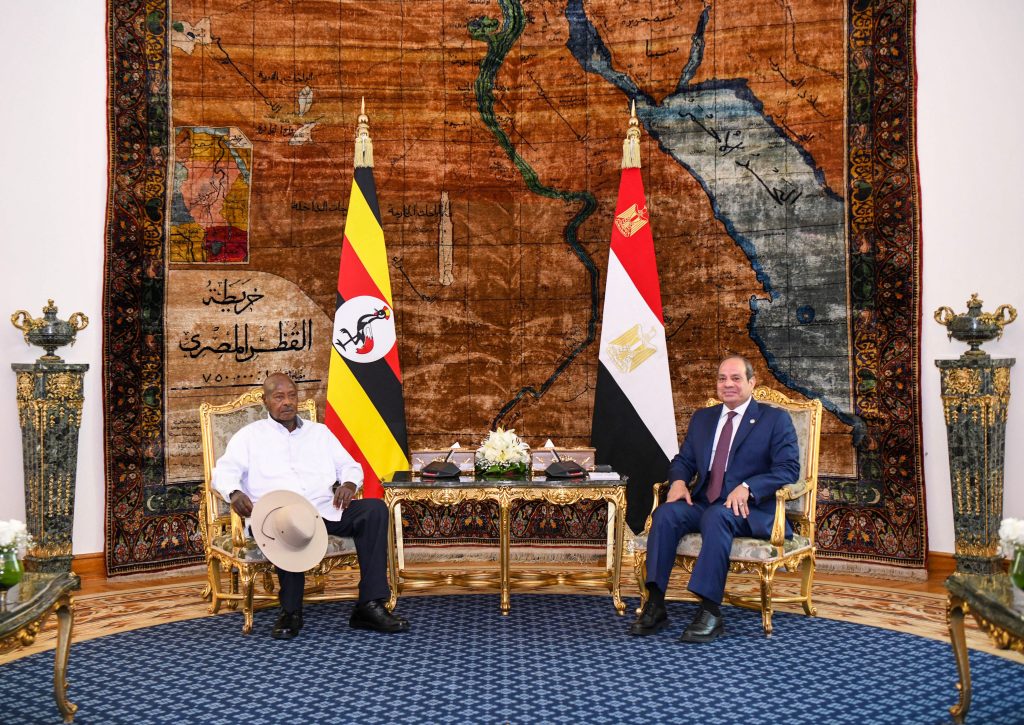

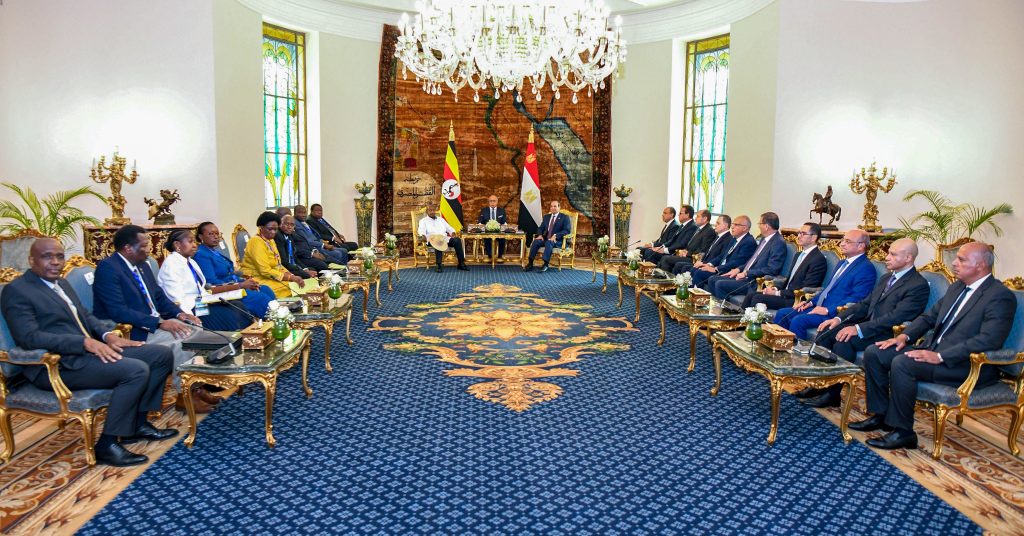

He made the remarks during a visit to Egypt, where he held bilateral discussions with his host, President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi. Museveni expressed gratitude to El-Sisi for the invitation, noting it had been a long time since he last visited the country.

Highlighting the historical ties between Uganda, the Great Lakes region, and Egypt through the Nile, Museveni traced the strengthening of political relations between the two nations to 1952, when former Egyptian leader Gamal Abdel Nasser assumed power.

“In our discussions, we addressed the future of the Nile. We must approach the issue of the Nile with a broad perspective,” Museveni said. “Rather than focusing solely on historical rights, we should consider the global needs of all Nile Basin countries.”

He stressed the need for a cooperative framework that prioritizes prosperity, electricity access, irrigation, and clean drinking water for all member states. Museveni argued that adopting scientific and fair methods would allow these goals to be achieved equitably.

The President’s comments come against the backdrop of long-standing disputes among Nile Basin nations over water rights and usage, particularly between Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia, amid the ongoing tensions surrounding the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

Egypt’s claim to historical rights over the Nile River stems from its dependence on the river for agriculture, economic stability, and survival, dating back to ancient civilizations.

The Nile provides about 97% of Egypt’s freshwater, critical for irrigating the Nile Delta and sustaining its population of over 100 million.

Historically, Egypt secured its position through colonial-era treaties, notably the 1929 Anglo-Egyptian Treaty and the 1959 Nile Waters Agreement with Sudan, which allocated 55.5 billion cubic meters of water annually to Egypt, about two-thirds of the Nile’s flow, while Sudan received 18.5 billion cubic meters.

These claims are contested by upstream nations, particularly Ethiopia, which argues that colonial agreements ignored the rights of other Nile Basin countries.

Ethiopia’s construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) since 2011 has heightened tensions, as it could reduce Egypt’s water share, especially during the dam’s filling phases. Egypt views the GERD as an existential threat, citing potential losses of 1 million jobs and significant agricultural output if water flow drops substantially.

Ethiopia, however, asserts its right to harness the Nile for development, as 60% of its population lacks electricity, and the dam could generate over 6,000 megawatts.

Other Nile Basin countries, like Uganda and Kenya, also challenge Egypt’s historical dominance, advocating for equitable water sharing under the 2010 Cooperative Framework Agreement, which Egypt and Sudan rejected.

Egypt’s stance is further complicated by its reliance on military and diplomatic leverage to maintain control, though recent negotiations, like the 2023 talks, show tentative progress toward cooperation, with no final agreement on GERD’s operation.

Museveni has previously positioned Uganda as an advocate for dialogue and shared benefit in transboundary resource management, calling for infrastructure and development solutions that benefit all parties dependent on the Nile’s waters.